Playful Healing

Yesterday, Diane who works for Wigan Athletic Football Club, came to visit the little organising circle that we host after Thursday coffee mornings. We had such a good time chatting all things play (well I did, that’s for sure!). It turns out Diane worked for the Wigan Play Team back in the day when play, whilst always the poor relation, had at least some resource. We had a great time reminiscing about the days when there were 32 community led play schemes running in communities during the summer holidays. Play schemes run by community members, who stepped back, when regulators demanded they must become qualified.

Anyway after such a great meeting I went home to think about the article exploring class that I’ve been asked to write for Context, the magazine for systemic family therapists, with my mind full of play.

I reflected on what’s been helpful in my own healing journey and what I’m noticing about the ways in which those around me in community are healing and organising.

I’ve always known the power of play in healing and was fascinated in my early 20’s by Dibs in Search of Self: Personality Development in Play Therapy by Virginia M Axline. I remember embedding some of the playful healing ways into the local play setting I worked in and watching magic happen alongside children as they played and healed. We didn’t measure them, write a plan about them, or sometimes even talk about the difficulties. We trusted the process and watching it unfold was the only outcome required. It certainly gave me a buzz that’s for sure.

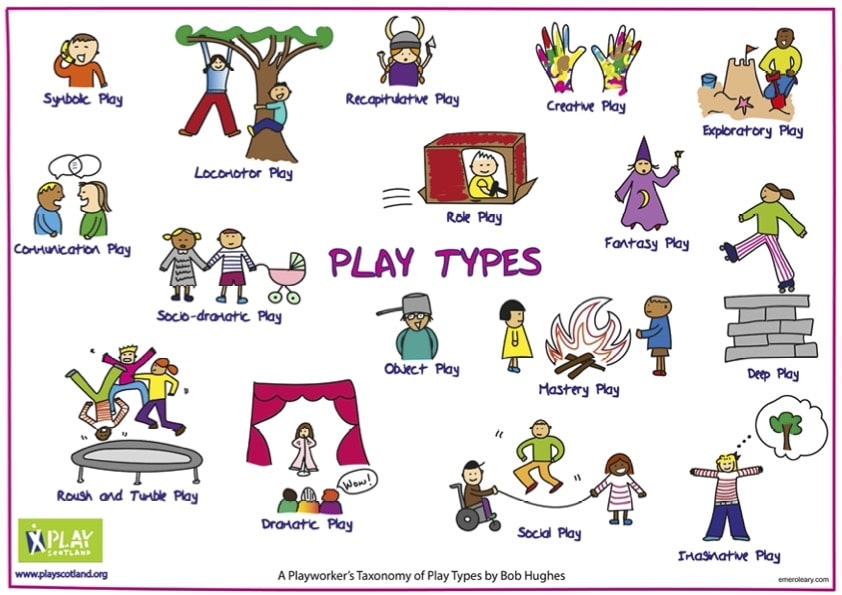

So my journey down memory lane took me to thinking about Bob Hughes play types. And I started to wonder why play therapy isn’t mainstream? Why isn’t it the primary methodology? Is it because children use their own resources and those in the environment to heal?

And, when did we decide that adults best heal through talking rather than playing?

I started to think about the famous quote Andrew Solomon shared from a conversation with a person in Rwanda.

“They came and their practice did not involve being outside in the sun where you begin to feel better. There was no music or drumming to get your blood flowing again. There was no sense that everyone had taken the day off so that the entire community could come together to try and lift you up and bring you back to joy. There was no acknowledgement of the depression as something invasive and external that could be cast out again.

Instead they would take people one at a time into these dingy little rooms and have them sit around for an hour or so and talk about bad things that had happened to them. We had to ask them to leave.”

That led me on to thinking about the current and traditional child protection system, and, the conflict that always exists between the needs of the child and the needs of the parent.

I remember this being a real conflict with the dominant and traditional system during our work in Wigan, when a great and brave team of people stepped outside of silos to try different ways of working with families. There was never any real space for parents to heal through play. Play was seen as something they do with their children. As if play as healing was frivolous or reinforcing ‘look she’s always putting her own needs first.’ (Fathers tended to get an easier ride.) Instead, parents had to heal in a block of talking sessions.

During my time alongside families, which has predominantly been within low income communities where poverty has taken its toll, I never really saw talking therapies work. Maybe, in a couple of instances, when the invitation was open ended and person led. I’m not saying we don’t need them at all, just that they should supplement rather than supplant community life and consider methodology. I found this in a dissertation submitted to the University of Chester for the Degree of Master of Arts (Counselling Studies) in part fulfilment of the Modular Programme in Counselling Studies in May 2016 by Alison Trott and it really resonated.

“Talking therapies are based on dominant white, Western, middle-class values (Sembi, 2006) which can, according to Holman (2014), discriminate the working classes since these individuals are often less skilled in verbalising and self-reflexion than their middle-class counterparts. Moreover, working- and middle-class accents and language-use are powered differently (Mindell, 1995) and utilise different speech patterns: the former using a restricted code, the latter an elaborated one (Bernstein, 1977), with research by Holman (2014) supporting this. According to Kearney (2010), accents and language can impact directly on how each hears the other, particularly where there is social class disparity, with stereotypical assumptions/JWBs being triggered: upper/middle-class oration is often perceived as ‘superior’, having status and conveying ‘expertness’ (Kearney, 2010), whereas regional accents/language are often perceived as inferior (Ballinger & Wright, 2007; Holman, 2014).“

I think that might be why I feel strongly about the idea of creating the conditions for community healing in all that we do in the local work, led by the people who live there, and, the importance of centring play and creativity in community healing processes.

You see I remember community play being beneficial for everyone involved. A bit like a tonic. Everyone had a right good laugh. The adults who organised it, got just as much out of it as the kids and everyone mucked in. That exhausted feeling at the end of play scheme when everyone came together as a whole to let what they’d achieved together sink in to the fabric of community life. That was in the days before we shifted to expert practitioners fixing broken kids and looking out for measuring goals and making every contact count. And, we call this progress!

Thanks to Play Scotland for the poster.