Why People Come Together-Part 2

This summer, whilst we were in full community Playbox flow, Jack Hunter came to visit for a day. We had a mooch around the neighbourhood and then settled in the park where we sat on the grass whilst Jack interviewed Angela for his research. Here’s Part Two of the edited interview. You can find Part One here.

Jack is a PhD researcher, living in Scarborough. His project is sponsored by York St John University and Joseph Rowntree Foundation and is focused on how and why people come together to take radical and transformative change in their local neighbourhood – and what might be done to nurture the soil in places where this hasn’t yet taken full fruit.

Angela

I’m not really interested in the reform agenda, I’m just interested in seeing if we can, like other places, own some of the stuff around here, make more decisions about some of the stuff round here and be a place where everybody feels that they’re able to contribute in some way. We’re starting to think about mental health community services, and in time we are going to run community alternatives to the child protection system. People are going to be paid round here to run our own stuff, to use their experiences and skills with their peers. And we’re going to have community led and properly resourced and proper paid jobs in care, you know, we’re going to do something about poverty in this area. If we make a change it will be to poverty.

Jack

Through jobs? And through…?

Angela

Owning. And just even if we could get people to spend one gram a week less on cocaine and bring that money back into the community, you know, if you think about the leaky bucket and if you look at what goes out. We spend a lot here on food ordering and food delivery. So that’s part of what we’ll explore when we get the shop, maybe a community kitchen and stuff like that.

We’ve just been doing small little things so far that encourage us to keep the wealth local and circulating and really promoting the ideas of community mindedness and community minded businesses. Part of the community awards is about community-minded businesses, and investing back into the local area. It’s helping community members see and experience what might be possible. If we get a Playbox, for example, if we manage to raise enough money for it, then we’ve done that ourselves. We’re not shaking hands with a benefactor or letting anyone else take the credit. We are doing it ourselves, together. If we do that then why can’t we collectively own land and buildings as well? Bring them back to the commons.

Jack Hunter

Yeah.

Angela

Why can’t we own and run some of the housing and supported housing? We know we could do a better job. Why should Serco have contracts round here? We could do a better job than them, you know. I think the possibilities are endless.

Jack

Yeah, of course. It seems you have projects elsewhere that you think are, like further down the line, or that you take inspiration from. Have you a sense of how they’ve come about, or what’s made the difference?

Angela

I think there are many different places around this country. I love Erika Rushton’s work and the work of Kindred. The way I’ve interpreted the underlying philosophy is that it doesn’t matter what your business structure is, it doesn’t matter if there’s profit in it as long as you’re socially trading. So let’s stop this idea of, like, CICs sit there, and another type of structure sits there. If we’re all doing stuff for the common good, it’s okay if you want to leave your house to your kids, or have a nice holiday. But let’s unite around the common good. And unite around wealth extraction. So many social enterprises are trapped in the land of grant funding. I like how Erika got me to consider, say, if you want to do youth work, how will you trade, and make the money that frees you from being trapped in the land of KPIs. There’s so much to learn from Merseyside, like Homebaked and Kittys Launderette and Squash. It’s liberating to find a way that doesn’t require begging bowls and having to smooch up to someone to get a grant.

Jack

To like charitable foundations or the local authority, or whatever

Angela

Yeah. And then once you’ve shifted the power, and you’ve got your trade, then the relationship with commissioners is far more adult, less paternalistic. So it’s a fundamental power shift. So I love what Erikas been doing and lots of others in Grimbsy, Hastings, Coalville, Plymouth. All over the place. I often see Jess Steele has a connection too in these places, and Frances Northrop.

We’re interested in care here. I’m really impressed with Mauricio Le Miller’s work, which started in America and now in Africa. His work is centred around resourcing peer networks. I’m really interested in things that put money, rather than service, directly into people’s hands and make change in that way, so I like what they’re doing. We are a long way from that being the norm but I’d really like to do some demonstration work in that space.

So there’s lots of people that I admire, but we don’t intend to copy and paste, like ‘Oh, we’re going do it in the way you did it’. We’re inspired by elements of different people’s works and then thinking about the local context here. Our guiding principles really are the touchstones of asset-based community development.

Jack

Okay

Angela

And the way in which you can just keep repeating those touchstones, starting at any point to unfold the next layer of community, and paying particular attention to community building. Asset-based community development connects the community from the place of strengths – what’s strong, what you love doing, your passions, and then once you’ve created those connections, then you become stronger in your communal spine to deal with some of the problems, and take on collective challenges. Community organising can tend to go for what’s wrong, and what shall we organize and campaign about? And it normally means, like, what do we want somebody else to do for us? It can overlook the internal resources. They are entangled and interconnected. With community building you’re creating spaces where lots of people who think very differently can learn to get along and be together. Finding the common ground, common concerns and what people might want to organise around grows beautifully in these spaces I’ve learned. But there’s very little resource around for building and authentic community development.

Jack Hunter

Yeah. Why do you think that is?

Angela

Because Community Development was stripped. And the places in which people used to associate. When we started here, and we started treasure mapping, it was very easy to see that the only place that people could freely associate was on the park bench, or in their own houses. Every space is now for hire and often filled by projects that aim to get you thin, stop you smoking or show you evidence-based practice about how to bring your child up. Or services themselves who’ve had to sell their building and have moved into spaces that once belonged to the community. There’s a risk of things becoming just service with no place for associational life. Asset-based community development will look and say let’s have a look at the strength of associational life, what do local people value. And if we build that first, then organising will naturally emerge. That takes long term resource instead of the short term funding initiatives with a little bit of organising bolted on, like Safer Streets for example. It’s easy to fund services to deliver short term projects and focus on engagement rather than development. It’s the boom and bust story and we need our public servant leaders to organise and grow some leader power as opposed to community power and say no to it. They need to organise.

With this Playbox here, right now in this park, it’s been a real opportunity to begin growing that muscle of collective care. When community members were posting on the Facebook group saying there’s young people on top of the Playbox we’ve been able to say, ‘Do you know them? Did you stop and have a chat?’, you know, like, trying to rekindle the idea that a function of a community is to collectively care for our young people. It’s our job, this is our job. What’s our role in this? That should be the first question, that’s the work. We’ve stopped asking that question and go straight to services. ‘Oh, we’ll bring a housing officer down, tell a Councillor, where are the Police?’ We’ve forgotten how it feeds our souls to care for each other. And when we remember, things start to change.

Jack

We talked about that before in the cafe about a public service mindset… Would you say that’s the default mindset in, in this community and most communities?

Angela

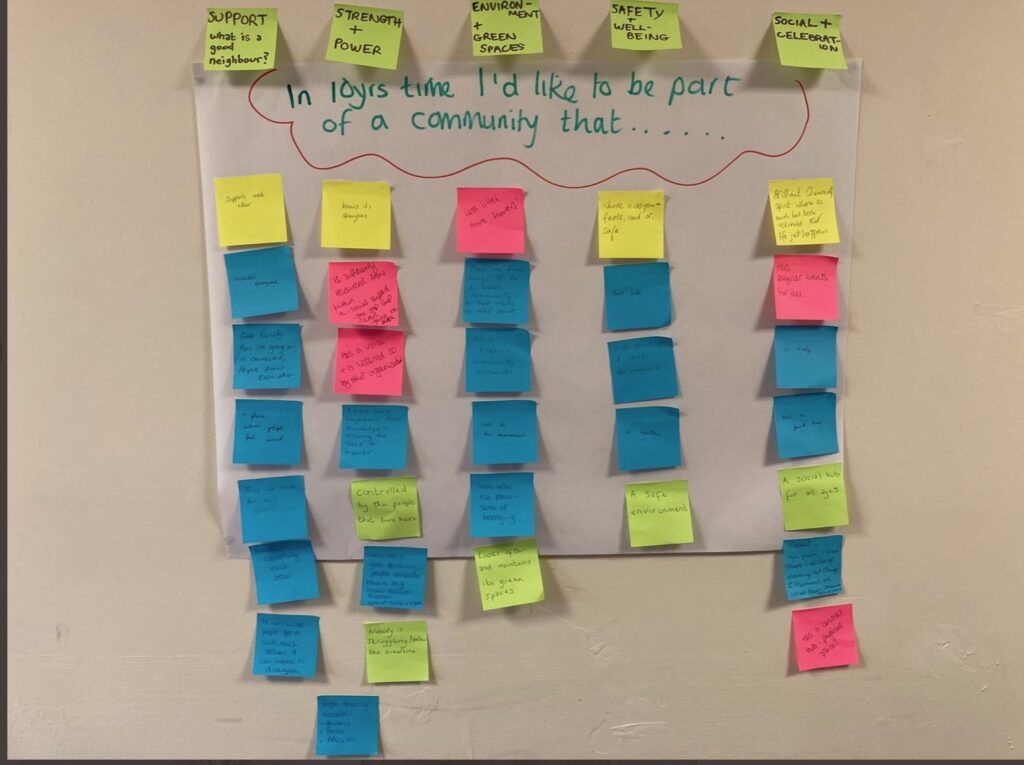

There’s the market obviously and its desire for us to consume. And I think that ideology seeped into institutions when thinking about how they might respond to the savage cuts. Managerialism within local institutions and when they got into behavioural insights and nudging, I think public servants saw themselves shift from being public servants to kind of, Greek Gods, looking down on us, wondering how they were going to nudge us into doing different things. They had some success and then went power crazy with it. And I think we had a shift around what we thought being a citizen was all about. So yeah, I do think it’s the default mindset and if we stand any chance of making a shift community work needs to be resourced. It’s a massive job. On my street, during the pandemic my next door neighbour, her dementia got worse because her family weren’t visiting. The initial response from people on the street was to go straight to services, rather than consider what can we do together as neighbours given that we live there 24 hours a day. So that’s why it needs resourcing because we’ve forgotten that we have a function as neighbours. You know, if you ask people: ‘What is the job of a neighbour? What is the job of a community? What’s the function?’ Try it, the responses are really interesting.

Jack Hunter

Yeah, that’s fascinating. Like, is that how you see your role? Do you think of yourselves as creating a good example of how the neighbourhood could be?

Angela

I think modeling? I think modeling and discovering other people who are like minded so that you can spread that about. So yeah, definitely. One of the things that we discovered quite early on was that people were just so frightened of rejection. If people didn’t smile back or say hello back. What if I asked my neighbor to do something with me and they said no, and in reality so many people are just waiting to be invited. And, is okay to say no and to receive a no, don’t take it personally. So even just offering that, we’ll come and stick some notes in doors with you or sit outside with you and chat with people as they pass. Offering a helping hand to get things going. Public living rooms are great for that.

Jack Hunter

Yeah.

Angela

But then there’s the charitable mindset. We need to get past that and the first step is owning it. Seeing that if our charity is predominantly about soothing the consequences of systems of oppression then we might be part of the problem. I think in minoritised communities, communities that have experienced oppression, communities that have had to fight, I see that mutuality is an everyday practice and people with first-hand experience of that could teach the charitable and voluntary sector a thing or two. I found that myth about ‘poor’ communities not organizing during the pandemic a little bit patronising. I mean, they’ve been organising and offering mutual support for years. Maybe they didn’t appoint a co-ordinator or use a spreadsheet because it was already rooted, natural practice in many patches.

Jack Hunter

Yeah,

Angela

And that’s what we are collecting stories about now as part of the systemic action research training we are doing alongside other Greater Manchester System Changers and the Institute of Development Studies. The overarching inquiry is ‘What are the current practices of solidarity, and how do they demonstrate conditions which bring to life an equitable and liberated GM?’ We’re collecting stories between August and January, then doing some causal mapping and ultimately forming some action research groups.

These are the stories that I’m wanting to really amplify about the way that this neighbourhood already does social work. The way that it already does banking. These systems that we need for transition are here, and they’re embedded within communities at the edge. They’re going to teach us how to justly transition. And, that’s kind of the work that I would love to hold up, I would love that woman over there to be teaching people how to do proper community-based social work, or just showing other people the way, or, just building more confidence in what she is doing herself and then being resourced for it, you know, whether it’s universal basic income, or some Maurice Lim Miller type of demonstration. I love the framing of it. The middle class have financially strong networks and they can afford to fail a few times. They can also have a side gig because there isn’t a benefit system telling them that they’re going to stop the money if they earn a little bit, or fear or having to get yourself back into the welfare system. So I think if we can bend the rules, or change the rules, in order to enable more people to get themselves out of poverty, because one thing that’s stopping a lot of people getting out of poverty is the system itself. So I’m interested in, how do we offer community-led loans or bursaries for education and how do we kind of invest in people with their own side gigs and their own businesses in a way that doesn’t get us sent to jail?

Jack Hunter

Love it. You’ve talked a bit about how you’ve come to here. How and why you’ve got to this point. And it sounds like to me, individuals such as yourself, and Gill, have played a big role in that, through your own personal, professional history, and then your disillusionment with what you’ve seen through those services. And that suggest, like, that the role of individuals is really important.

But there’s also obviously the pandemic, which was maybe a bit of a shock to the system and maybe allowed a bit more freedom or a bit more of a boost to catalyse things into action…

Angela

Interestingly, you’re right, some of the pandemic has been responsible for it, because like the community I mentioned before in Netherton before the pandemic, we’d been trying for a good number of years to think about the community taking on the community centre, and there was a lot of fear. And then after the pandemic, when they’d practiced social work, and they organised the community led response, you just saw the shift you know? So people need experiences, small experiences of success to build the foundations of possibility and exercise the imagination muscle. Reminding themselves that they are able after years of being labelled and rescued. I think here we were definitely intentional about talking about the way we do things. And we’ve been true to that. And it’s tricky. Fixing is so addictive for the fixer and helps to soothe unmet needs. Stopping fixing means we have to look at ourselves and our own messiness. And we’re thinking about ensuring everything that we plan is always a little bit shit, purposefully, because if you’ve got something slick you’re a participant or a customer. You don’t walk away thinking, they need me. if you go to something that’s not quite polished, there’s a role for you. And that’s how we pick most people up, you know. It shifts from being needy to being needed. And then people start to notice, like ‘you’re doing that on purpose aren’t you?’. And then they start doing that, creating space for others to step in and step up. If you’re intentional, and go at the speed of trust all kinds of wonderful and unimagined stuff begins to emerge. And then the dominant system feels threatened and attacks or wants to absorb it and scale it. The work never stops. Holding the line. And taking your time. Going at the speed of trust is something I definitely picked up from Cormac Russell and in practice it’s really tricky.

Jack

What do you mean?

Angela

Like, noticing when you’re wanting to push things quicker than they are naturally ready for – messing with the eco system. Oh, couldn’t we do this and couldn’t we do that? Maybe we could have five houses now. I wanted this Playbox last year. If that had happened, it wouldn’t have like worked in the way it has done because of the relationships that have been built. And I think we might have been seen as a service coming in, rather than community members. So I think going at that slow speed and letting it be messy you know, be prepared to let things fail and not rescue people you know, hold them up and be with them and, get stuck in when you’re there. Being comfortable with uncertainty and emergence and like flow and that’s a skill in itself that not everybody has. And just really tuning in and listening.